Behind Closed Doors: Undocumented domestic violence survivors face extra challenges — but there's help (Part 2)

This project was originally published in KCBX with support from our 2023 Domestic Violence Impact Fund.

Many people escaping domestic violence come to Lumina Alliance for help.

Melanie Senn

Intimate partner violence includes behaviors that are meant to control, frighten, manipulate, or physically hurt a partner — and sometimes the abuse is sexual. In this second episode of a three-part series about domestic violence in San Luis Obispo County, KCBX reporter Melanie Senn spoke with advocates about the extra barriers undocumented survivors face and how difficult it can be to leave.

__

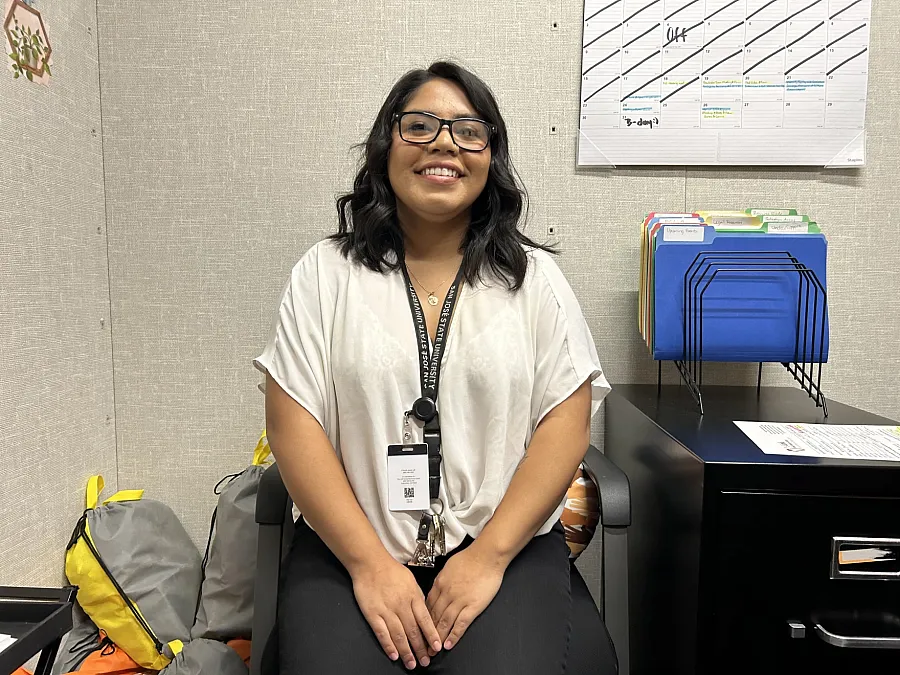

At The Link Family Resource Center in Paso Robles, advocates were ordering food, as they do two mornings a week, to stock the food pantry. Arlen Merced is one of them.

“We usually serve around, I want to say, more than 300 families a month,” Merced said.

All of the advocates at The Link are bilingual in Spanish and English.

“So the Spanish speaking community feels comfortable coming with us,” she said.

Arlen Merced, Family Advocate at the Link Family Resource Center.

Melanie Senn

Merced has been working at The Link for two years. It’s becoming well known as a place families can come for support with finances, legal hardship, and food insecurity. Link advocates can also get help for people, including undocumented people, who have experienced sexual assault or are experiencing domestic violence.

Merced, who is 25, knows too well the barriers these individuals are facing. She’s dealt with all of them: the undocumented status, sexual assault, and intimate partner violence. Merced arrived in the United States from Mexico at the age of 7. She is undocumented, though she’s a DACA recipient. The sexual assault happened at a fraternity house.

“It was my third year of college,” she said.

The rape almost derailed her from finishing at San Jose State University. Her situation worsened when the boyfriend she’d dated since high school became physically aggressive.

“I did grow up seeing some domestic violence. I just thought, well, an argument's going to happen, and somebody's gonna get hit. And so that's why, when I went through my own sexual assault, I thought, 'I can't fight back because, what if it gets worse?'” she said.

Against the odds, Merced became the first person in her family to earn a bachelor’s degree. Afterward, she moved back to Paso Robles and reached out to Lumina Alliance, which helps people affected by sexual assault or domestic violence.

“My first therapy was just crying and crying. I was holding on to so many things for so many years. That was the only way that I could start healing,” she said.

These difficult experiences compelled Merced to help others. She told me about one particular woman who came to The Link for support. To respect the woman’s confidentiality, Merced told me I could call her Milagro, which means miracle in Spanish. Milagro was allergic to her husband’s semen, a little-known condition that is painful and can be life-threatening — she’d been to the emergency room several times. The condition is entirely preventable with condom use. Milagro’s husband refused to wear one.

Merced said she asked Milagro if she’d talked to her husband, “you know, letting him know this happened when they had intimacy.”

Milagro told Merced that her husband didn’t care, that because she was his wife, it was her responsibility, her duty.

Angie Gonzalez, the advocacy manager at Lumina Alliance, said that, oftentimes, survivors who have experienced intimate partner violence have also been sexually assaulted by their partner.

“The narrative they had formed in their head was, ‘This is just how things are. And I can't complain, I have to accept it. If my partner wants to have sexual intercourse, I don't have a say whether I can say yes or no,’” Gonzalez said.

Angie Gonzalez is the Advocacy Manager at Lumina Alliance.

Melanie Senn

Gonzalez said that in the Latino community, intimate partner violence is normalized.

“We don't talk about it. It's something that happens behind closed doors, and it stays behind closed doors,” she said.

Milagro, however, was ready to be free from her husband’s abuse. Merced took on the challenge of helping her file for a restraining order online. But as Milagro got closer to leaving, her husband stalked her and threatened her. She feared he would take their three children to Mexico. In the end though, she got the restraining order and was able to move out. Merced secured financial assistance for Milagro through Lumina for rent and helped her get a job. Finally free, Milagro could begin to heal and to live independently.

“I remember the last time I saw her,” Merced said, “we were talking about how proud we were of each other.”

It’s challenging for anyone trying to get out of an abusive relationship, to leave and put their life back together. Angie Gonzalez said that the situation can be extra difficult for undocumented people, as they may not have transportation or a bank account; they may not be able to secure affordable housing without a credit score. Even worse, she imagined, is the fear.

She said she imagines they might think, “‘I don't necessarily speak the language. And if I reach out, are they going to ask me if I'm here illegally? If I call law enforcement, are they going to be able to assist me? Or are they going to deport me?’ And so there is a lot of fear, a lot of just a lot of barriers,” Gonzalez said.

Luckily, there are caring, compassionate people in the county who know that people — all people — suffering from intimate partner violence need help. And they’ve made it their life's work to provide it.