Part 3: In LA’s fentanyl epidemic, MacArthur Park community bears the heavy burden

This project was originally published in Los Angeles Daily News with support from our 2023 California Health Equity Fellowship.

A person wakes up and leaves a Los Angeles alley in the MacArthur Park neighborhood where people often smoke fentanyl.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

It’s 8 a.m. in MacArthur Park.

A local shopkeeper hoses down his front stoop, washing away the layer of debris that accumulated overnight.

As water strikes the already hot asphalt, steam rises and mingles with clouds of smoke coming from a group of people slumped on Alvarado Street. A mother shuttles her two young children past the huddle, weaving through dozens of vendors to reach the playground.

The majority Latino, working-class community has adapted to life around one of the largest fentanyl markets in Los Angeles — but not without paying a price.

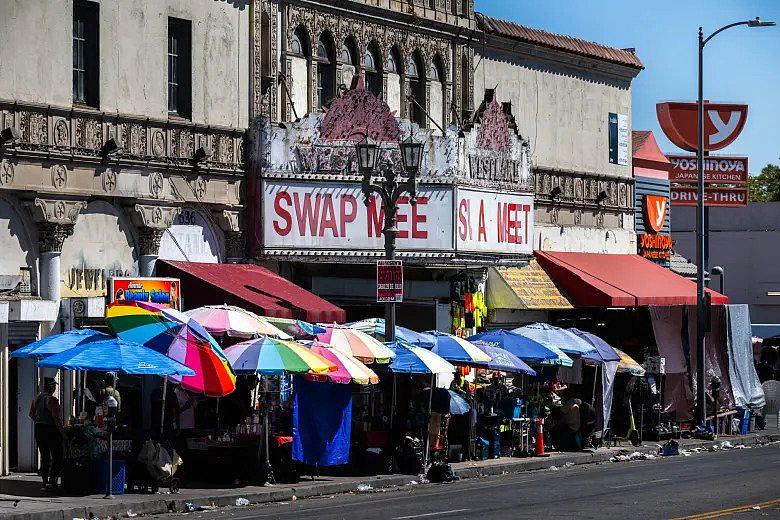

A vendor brings his wares to Alvarado Street across from MacArthur Park.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“The worst thing about MacArthur Park is the fentanyl epidemic,” says Rafael, a street vendor who sells kitchenware and declined to share his last name. “I’ve seen people die in the park. I’ve seen people sacrifice everything for a little euphoria.”

In the past three years, MacArthur Park has become a hub for fentanyl sales and consumption – a phenomenon driven, in part, by an underground trade in shoplifted goods that people use to make money for the drug. Local businesses now battle a spike in theft, while open-air drug use deters residents in the densely populated neighborhood of Westlake from enjoying their largest park.

People frequently overdose and die.

Raphael, 62, sells cookware on Alvarado Street.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“I used to go down the street to go buy a cup of coffee in the mornings,” says Sylvia, a Spanish speaker who also did not want to her last name published because of safety concerns. “But now, I don’t do that because I need to cross an alleyway and there is too much trash and it is full of people doing drugs.”

Her family has run a vitamin and medicine stand inside a swap meet by MacArthur Park for more than 25 years.

“Even the common people, Latinos that live in this area, are scared because they have been hurt,” she says in Spanish. “There are a lot of crazy people out here.”

Rachel Michelin, president of the California Retailers Association, receives frequent shoplifting complaints from businesses near the park.

“One of the problems we continue to see in MacArthur Park,” Michelin says, “is that people are going into stores, they steal items, they go out, they immediately sell it, they buy drugs, they go back and they steal again.”

Carlos, 16, helps out at his family’s jewelry and antique store on Alvarado Street by watching multiple cameras that are set up in the store and on the street where vendors crowd the sidewalks.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Fentanyl is a highly addictive, synthetic opioid about 50 times as potent as heroin, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The last few years have been marked by a rapid increase in the number of people selling and using fentanyl around MacArthur Park, says LAPD detective Ben Yi. Street vending has also grown exponentially in the area since 2019, when a state law decriminalizing the practice was enacted, says LAPD Detective Stephen Beerer.

The two groups – vendors and people who use fentanyl – have an interdependent relationship.

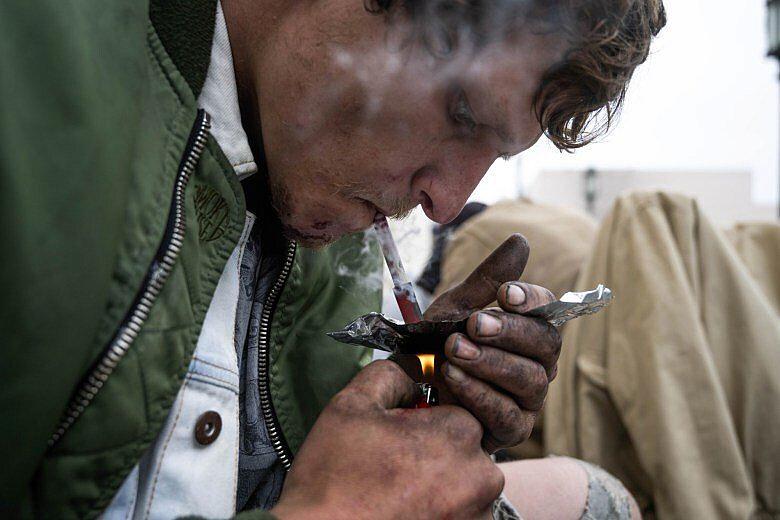

Matthew, 30, who uses fentanyl in an alley near MacArthur Park says he first got hooked on oxycodone at his Pennsylvania high school.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“The worst thing about MacArthur Park is the fentanyl epidemic. I’ve seen people die in the park. I’ve seen people sacrifice everything for a little euphoria.”

Rafael, a street vendor

People often make money to buy the drug by shoplifting goods and selling them to street vendors, Beerer says. Many vendors then resell the stolen products to try to make a living, he adds.

Not all vendors are part of this trade; some sell homemade foods or wholesale goods. Some vendors are experiencing housing instability themselves and are doing the best they can to get by, says Raphael, the kitchenware vendor.

“That culture was always here,” says shopkeeper Lillian, referring to people selling stolen goods and drugs near MacArthur Park. “But I feel like it just blew up and now it’s in everyone’s faces. It’s not lingering in the shadows or in the corner alleys anymore.”

Several local business owners also say the increase in shoplifting — and in vendors hawking shoplifted goods — is hurting their mom-and-pop ventures.

“People don’t come inside the swap meet that often, and I think it’s because there are too many people outside selling products on the street,” says Sylvia, the vitamin seller. “I know that they sell similar products for cheaper outside.”

Umbrellas blanket the sidewalk where vendors sell everything from drugstore items to clothes, food and electronics on Alvarado Street across from MacArthur Park.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“People come in almost every day to steal. We try our best to stop them, but when they get angry, then it becomes dangerous for us. They steal everything: clothes, food, ice cream.”

Rosa, store manager at Laguna Market

Laguna Market is a family-owned grocery store that has operated near MacArthur Park since 1983. But in the past two years, it has seen a big jump in theft, store manager Rosa says in Spanish. She also did not want her last name published because of safety concerns.

“People come in almost every day to steal. We try our best to stop them, but when they get angry, then it becomes dangerous for us,” Rosa says. “They steal everything: clothes, food, ice cream.”

Year-to-date property crime is up in LAPD’s Rampart Division, a 5.5-square-mile area including the communities of MacArthur Park, Echo Park, Silver Lake, Angelino Heights and Pico-Union. In the 180-day period from Feb. 19 to Aug. 17, there were more than 500 incidents of burglary, theft, robbery and vehicle theft reported within a half mile of MacArthur Park.

“People started getting the hint, ‘Hey, there’s no consequences to this’,” says detective Beerer, referring to repeat property crime offenders.

Michelin and Beerer both point blame at Proposition 47 for enabling this cycle.

The state ballot measure, which voters approved in 2014, reduced most drug possession offenses and thefts of property valued under $950 from felonies to misdemeanors. The aim was to stop locking people up for low-level crimes and reinvest the cost savings into substance use, mental health and housing programs.

Michelin says she supports the intent of Prop. 47. But she also says she believes the supportive services have failed to reach enough of the target population to effectively deter property crimes.

A person sleeps sitting up in a Los Angeles alley known for fentanyl use.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“There were changes that needed to be made to our criminal justice system,” Michelin says, “but I think when it comes to this piece on retail theft, I don’t think they (lawmakers) understood the unintended consequences that we’re seeing today.”

A 2018 report on the statewide impact of Prop. 47 found evidence that it decreased recidivism rates among those who committed drug possession and shoplifting offenses. Property crime increased, but there was no evidence, according to the report, that the proposition led to an increase in violent crime.

Prop. 47 remains popular among many Democratic politicians. In 2022, a proposed bill to repeal most aspects of the proposition and another to lower the felony threshold for shoplifting back to $400 both failed in the California State Legislature.

Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez, who represents MacArthur Park, is among the many politicians opposed to repealing Prop. 47. From her perspective, the lower felony threshold locked people up for an unnecessarily and cruelly long time and made it harder for them to reintegrate into communities due to their criminal record.

“I just don’t believe that that policy made us safer; it wasted our money,” she says. “Right now, we should actually be doing the legwork of providing more safety nets for folks.”

Hernandez supports investing in diversion programs that offers perpetrators of certain low-level crimes supportive services in lieu of punishment, she says.

There is already a Prop. 47-funded outreach team in MacArthur Park working to connect people who have a criminal history with programs that provide substance use treatment, mental health services and housing resources.

The team was launched in February 2020 as part of the L.A. city attorney’s “Los Angeles Diversion, Outreach, and Opportunities for Recovery” program, or LA DOOR. It operates in five different “hotspots” on a weekly basis and consists of seven case managers, a nurse, a substance use disorder counselor, a therapist and a field supervisor.

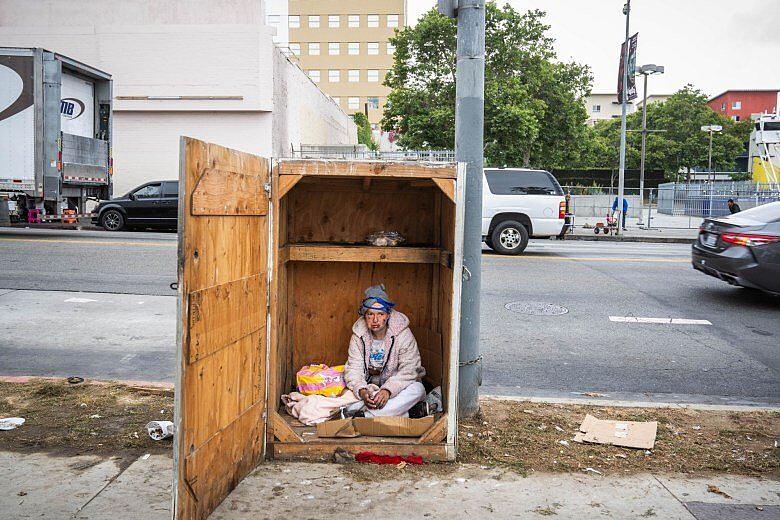

A young woman wakes up in a shipping box along MacArthur Park, where drug use is rampant.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Its impact around MacArthur Park has been positive, but limited.

During more than three years of effort, only two clients were placed in residential substance use treatment and two in permanent housing, while six clients received other forms of substance use treatment and 24 received temporary housing or shelter placements.

“It is challenging to have a meaningful interaction with someone deep in the throes of active fentanyl use.”

Ivor Pine, spokesperson for the L.A. city attorney’s office

In addition, 36 clients received basic necessities such as food, clothing and documents; 11 clients were connected with basic medical care; and nine clients with mental health services.

Ivor Pine, spokesperson for the L.A. city attorney’s office, says these numbers are probably an undercount. He notes that when the program was launched, data on which LA DOOR clients came from the MacArthur Park hotspot was not properly captured, but has since been remedied.

Fentanyl addiction has also proved a big barrier in connecting clients to services, Pine says.

“It is challenging to have a meaningful interaction with someone deep in the throes of active fentanyl use,” he says.

“People are much less likely to agree to get help for their addiction,” he adds, and “due to fentanyl’s potency, users become fully addicted much faster than (with) other drugs.”

For many people who are homeless around MacArthur Park, their day revolves around obtaining fentanyl and staving off withdrawals, says Rita Richardson, program supervisor for LA DOOR’s MacArthur Park team. This leaves little time or energy for engaging with outreach workers, she says.

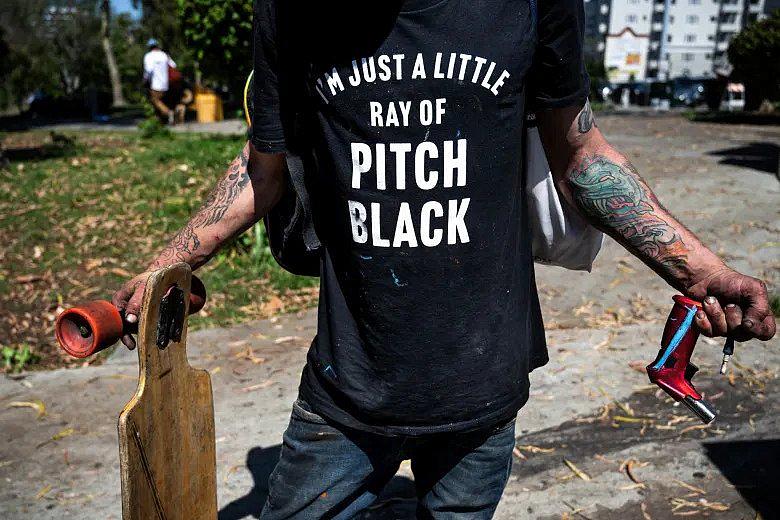

Joseph, for example, is unhoused and says he tries to make at least $100 a day, by reselling shoplifted goods, to buy fentanyl. Others who use fentanyl in the area report that they need anywhere from $20 to $150 a day.

With his butane torch and dabber in hand Joseph, 32, says he went from an all-star athlete in Florida to homeless and addicted to fentanyl. He says his habit costs over $100 a day.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Joseph was a bright kid and four-season athlete who dreamed of a professional sports career.

He was studying physics and playing soccer at the University of South Florida when he sustained an injury on the field and was given opioid painkillers. Once his prescription ran out, he began buying pain pills on the street. That turned into buying heroin.

He came to Los Angeles for a rehab program about a decade ago and was in and out of treatment for most of his early 20s. Now at 32, he has been homeless for six years and has been addicted to fentanyl for the last four, he says.

“I try to be as polite as possible when I’m in the stores, and I despise that I’m in the situation I’m in,” he says. “It’s a mixture of big pharma and my own irresponsibility.”

Several hundred people use fentanyl around MacArthur Park on a weekly basis, says outreach worker Jennifer Haid. They all have stories like Joseph’s.

In response to the growing need for help at MacArthur Park, more homeless service organizations — including PATH, Urban Alchemy and the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority — have been offering services in the area, says Richardson. Councilmember Hernandez says she’s working on bringing a mobile overdose prevention team and a homeless services center to the area.

Grassroots organizations are also trying to make an impact. Local church groups perform park cleanups, and in April 2022, nonprofit organization DePaul USA opened a day center that provides services, including free breakfast, showers, and referrals to medical and substance use treatment.

In 2020, Haid established the nonprofit Humankind LA to help people living around MacArthur Park get housing. One of her key partners is local shopkeeper Lillian, who safely stores documents and IDs for Haid’s clients and lets them use the store telephone.

A homeless man who uses fentanyl visits the Casa Milagrosa resource center for breakfast in the MacArthur Park neighborhood. The center also serves day laborers and low income individuals.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Still, the scope of the homelessness and fentanyl crises is outpacing the services offered.

Jennifer Gill is a 25-year MacArthur Park resident and has spent years working to improve the community, first as vice president of the no-longer active neighborhood council and now as a member of the City of Los Angeles MacArthur Park advisory board.

In January and February 2021, she was thrilled to see then-Councilmember Gil Cedillo lead an initiative to clear the park of encampments and move more than 250 people into shelter.

This allowed major improvements to be completed in the park, but was criticized by some advocates for disconnecting unhoused people from networks of support.

Initially, Gill says, she saw the intervention as a fresh start for her neighborhood and for the people who lived in the park. But now, she says, there are more homeless people around MacArthur Park than before the clean-up.

“I get disappointed sometimes,” she says, “because it really is such a beautiful park.”

A young man sleeps in MacArthur Park. Homeless people say their belongings are often stolen while they sleep.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG