Mobile health care providers play crucial role in obstetrics for rural expectant parents

The story was originally published by the KUNR with support from our 2023 National Fellowship.

Dr. Catherine McCarthy walks into the Barnett Clinic at the South Lyon Medical Center, where she works out of once a month to provide women’s health services, in Yerington, Nev., on Nov. 13, 2023.

Kat Fulwider/KUNR Public Radio

Family physician Catherine McCarthy started her day at 8 a.m. in Reno by loading a bin of paper patient health records and a duffle bag with medical supplies into the trunk of her all-wheel-drive Acura MDX. As she drove on Highway 95, hills of sagebrush lit by an orange glow from the early morning sun marked the way to Yerington. It’s a trip she has made once a month over the past 20 years.

“There is no prenatal care or women’s health care provided in the greater Yerington area,” she said.

McCarthy, also a family medicine professor at the UNR School of Medicine, is typically joined by a resident physician and medical student. They set up at the South Lyon Medical Center to provide services such as pregnancy confirmation, cervical cancer screening, and birth control.

McCarthy makes the more than one-hour-long trip because many of her patients can’t travel to Reno.

“Some of my patients don’t have c

Dr. Catherine McCarthy drives along Highway 95 through Silver Springs to get to the South Lyon Medical Center in Yerington, Nev., on Oct. 16, 2023.

Lucia Starbuck/KUNR Public Radio

ars, or their car isn’t running, or they don’t have money for gas to drive both ways. Or if they’re employed, they may not be able to get off work to make all those trips up,” McCarthy said. “And then we know that in the winter months here, the roads can be very precarious.”

Rural communities rely on traveling providers like McCarthy in order to maintain certain types of care.

Dr. Catherine McCarthy holds a pregnancy wheel, also known as a gestation calculator, at the South Lyon Medical Center in Yerington, Nev., on Nov. 13, 2023.

Kat Fulwider/KUNR Public Radio

Certified nurse midwife Abby Rizk travels from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City to Elko every two weeks for the Elko BirthCare HealthCare Clinic. She leads a team of midwives who provide low-risk prenatal, postpartum, and gynecological care for residents of Elko and surrounding areas who give birth at the University of Utah Hospital.

“There were so many women who did not want to give birth for their own reasons in Elko and were making the three-and-a-half-hour drive to Salt Lake City to give birth, and we thought this would be a way to ease the burden,” Rizk said.

In addition to mobile providers, rural emergency medical services play a huge role in maternal health care. This is especially true in Nevada, where Washoe and Clark counties are the only places with neonatal intensive care units. NICUs are for babies that are born early or have health complications and require special care.

MedX AirOne, an air and ground ambulance service based out of Elko, is also present in Winnemucca, Ely, and Wells. EMS director Jacob Dalstra said they respond to maternity calls about once a week.

“We have had to utilize a flight team to transport moms that are going into labor in a very rural community that has no care facility at all,” Dalstra said. “We’ve also done rendezvous, especially in very rural places, where we’ll actually meet them in the middle with the ambulance.”

Having a baby flown can be very scary and traumatic for new parents, but in Nevada, it’s a reality, Dalstra said.

“In movies and TV, people think that only if you’re dying, you’re going to be placed in a helicopter. Well, that’s not always the case in rural Nevada,” he said. “We have to utilize helicopters and airplanes to get moms the care that they need.”

MedX AirOne EMS director Jacob Dalstra in Spring Creek, Nev., in December 2022.

Courtesy Of Serenity Orr/MedX AirOne

Many rural EMS providers are volunteers, and due to the geographic distances and the unpredictability of childbirth, some babies are born in ambulances. That was the case for retired emergency medical technician Patty Browning. She lived in central Nevada for most of her life and didn’t make the one-hour trip to the hospital when she gave birth to her first child in 1987.

The helicopter landing area at the South Lyon Medical Center in Yerington, Nev., on Nov. 13, 2023

Kat Fulwider/KUNR Public Radio

“We lived in Round Mountain and she would have been delivered in Tonopah. That’s where my OB was. And we did not make it. We made it to about 14 miles outside of Tonopah. She was born with an ambulance crew that had been my EMS instructors,” Browning said.

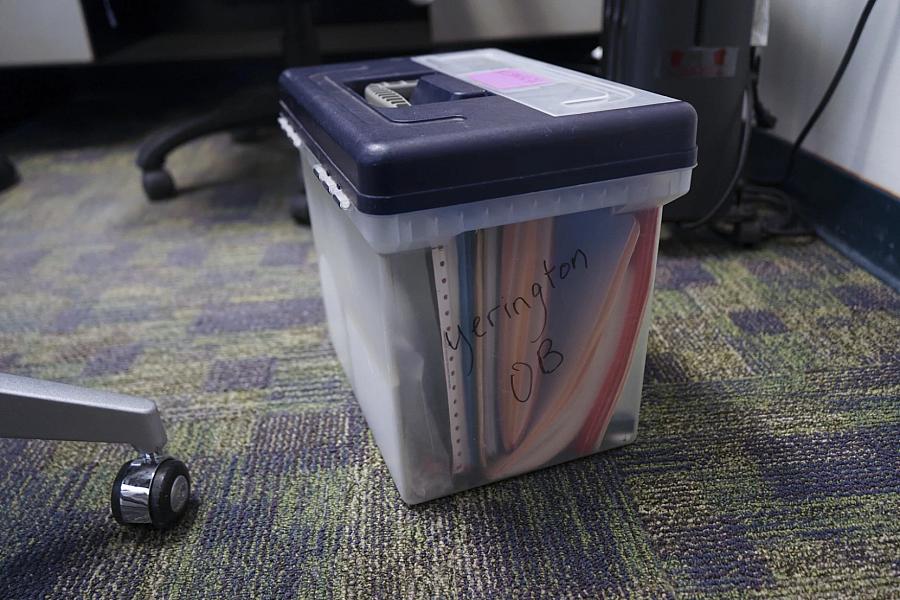

Dr. Catherine McCarthy’s patients’ health records that she brings from Reno to the South Lyon Medical Center in Yerington, Nev., on Nov. 13, 2023.

Kat Fulwider/KUNR Public Radio

She proudly shared that her daughter’s birth certificate is unique.

“Her birth certificate actually notes that she was born at Mile Marker 14 on Highway 376,” Browning said. “It’s a fun birth certificate that will follow her through her life.”

Members of the ambulance crew are listed as the attending physicians.

The hospital that Browning was on her way to, Nye Regional Medical Center in Tonopah, shut its doors in 2015.

Back in Yerington, McCarthy pulled up to a parking space for visiting physicians. The clinic McCarthy works out of is connected to the South Lyon Medical Center’s urgent care and emergency room, but there is no full-time OB-GYN. The majority of her patients give birth in Reno or Carson City. She said that continuity of care, or seeing a provider you’re familiar with, is important.

“Many of my patients I’ve taken care of for years through multiple pregnancies,” McCarthy said. “We’ve taken care of sisters and multigenerational families.”

On this day, McCarthy had a patient scheduled every 30 minutes, but she had several no-shows. Over the last two decades, she’s learned that patients simply forget, so she picked up the phone and started making calls.